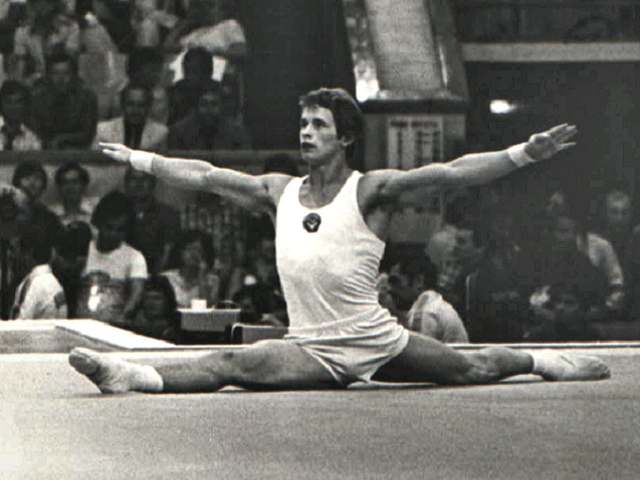

Aleksandr Dityatin won eight medals at the 1980 Olympics, three of them gold. He achieved a rare feat of medaling in every single of the six event finals. TeamRussia interviewed him to commemorate 40th anniversary of the Moscow Olympics.

Q: You came to the Olympic Games as the reigning World all-around champion which you became in 1979 in Fort Worth. Were you expected to win again?

A: Of course. I expected it too. Because I was properly prepared.

Q: At the time, it was common to pledge [to achieve something] at Komsomol meetings…

A: And we did, promising to surpass the medal goals. And we achieved that because we were stronger than our competitors. That was generally applicable to the whole team. I don’t really remember now how many medals we were supposed to win at the Olympic Games at home. Regarding individual performances, I wrote in the annual individual plans – to place in the top three at the World Championships or Olympic Games. After all, both you and your competitors can make mistakes.

Q: What was your favorite event?

A: Rings. I won silver on rings when I was 18 at the 1976 Olympic Games, losing only to Nikolai Andrianov.

Q: And what event was the hardest for you?

A: All of them were hard, but none were my weak events. That’s why I made the Guinness Book of Records.

Q: 2018 World AA champion Artur Dalaloyan is sometimes let down by pommel horse. You always managed to do it despite your height – 1.8 meters. Meanwhile, it’s supposed to be harder for gymnasts with long legs to do pommel horse.

A: It’s all just stories. Consistency doesn’t depend on height. Training, being prepared for a competition, and mindset are the decisive factors.

Q: At the Montreal Games, you lost the bronze in the all-around by only 0.05. Were you upset?

A: So much that I wanted to gnaw on iron.

Q: What did you lack [to win]?

A: Judging decisions. After all, judging is subjective in gymnastics.

Q: You didn’t have enough authority?

A: You could say so.

Q: On which event were you unfairly judged?

A: I don’t remember that I was judged unfairly there, but others got scores that were too high sometimes. In Moscow, I competed as a winner of two World Cups and the reigning World all-around champion. It’s a different status.

Q: At the Moscow Games, Nikolai Andrianov was the team captain. What was his role?

A: Nikolai was older and more experienced than everyone. He turned 27 by then, Makuts was 20 and the rest were 22. I turned 23 a few days after the end of the Games. Andrianov could give some advice but ours isn’t a traditional team sport where the captain can be a conduit for coach’s ideas on the field or court. In gymnastics, you step onto the competition floor alone.

Q: In the end, in the all-around, your main rival was your team captain who won silver.

A: I was in the lead after the qualification and then widened the gap, winning almost half a point over Nikolai. I managed to deal with anxiety and did all the events without mistakes.

Q: What was your reaction to the fact that competitors from Japan and USA didn’t come to Moscow? After all, they won team medals at the 1979 World Championships and before that, Japan had been consistently winning World Championships and Olympic Games since 1960.

A: We felt sorry for the athletes. We knew that they worked hard for it. Half a year before the Olympics, the talks about the boycott started but they kept hoping. Some never managed to get to another Olympics.

Q: Did they later say they were sorry they didn’t come to Moscow? Did you talk to them about it?

A: What would be the point? We talked at competitions but our talks were reduced to “How are you? How’s your family?” We wished each other luck and didn’t bring politics into it. Moreover, you need to know the language well in order to discuss such questions. On the other hand, you couldn’t go abroad by your own choice in the USSR. Now it’s possible, if you want to, to go for a visit to America or England and have a heart-to-heart: “Yes, it’s a pity it happened this way…”

Q: The artistic gymnastics competition took place at the very beginning of the Olympics Games. You didn’t participate at the opening ceremony, did you?

A: We watched it on TV. We could still see that it was a grand and colorful spectacle.

Q: But you probably participated at the closing ceremony, right?

A: No, I didn’t either. A couple of days after the competition, we went home which we had not been to for a long time. There were camps, competitions, and camps again. We spent the last month [before the Games] training in Minsk where we were given the Palace of Sports with a podium. We only came to Moscow a few days before the start of the competition. We traveled by train, in a separate coach guarded by the police. We moved into the Olympic village like the rest of the athletes and trained according to a strict schedule. Each team was given specific time on the podium and in the training gym. Everyone was under the same conditions.

Q: How were the winners honored?

A: I was awarded the Order of Lenin. I learned about it while on a tour in Latin America. A telegram came to the Soviet Embassy in Argentina with a decree about awarding Dityatin and other gymnasts. And for the Montreal Olympics, I was awarded the Order of the Badge of Honour.

Q: But what happened right after your victory in Moscow?

A: When I came back to “Peter” [1], no one even came to greet me. I took a cab to get home.

Q: Was there some sort of a miscommunication?

A: You’d have to ask the people who were in charge then.

Q: I’m afraid they’re unreachable now.

A: That’s for sure. Of course, we were honored. We went to all sorts of events, met with people. At the Komsomol conference in Leningrad, I was given a huge Olympic Mishka. I still have it.

Q: Were you offered any leadership positions?

A: I was already a member of the regional Komsomol committee and was on the Leningrad City Council for two years.

Q: Are you still in touch with any of your teammates from the Moscow team?

A: Markelov who lives in Moscow and I call each other sometimes. Before the perestroika, we would all meet from time to time. And we saw each other at competitions, especially since Tkachev and I were both judges. We worked at big competitions – USSR Championships, Spartakiade, Moscow News, World Cups.

Q: You kept working as a coach until the mid-90s when you started working at the Border Service. Did you decide that coaching wasn’t for you?

A: Everything was falling apart in the 90s. The team I coached fell apart, too. I had adult guys, Masters of Sport. They needed to eat, so they started working. I had been a border guard since 1978, I did my army service at the sports division. In order to get a pension, I needed to work for one more year and I got a job at the Pulkovo Airport. In the end, I worked there for seven years, became the department head. I retired in the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. At the same time, I graduated from the State Service Academy and became the chair of the Gymnastics department at the Pedagogical University in 2002.

[1] “Peter” is a common colloquial name for St. Petersburg/Leningrad/Petrograd (that city sure had many names over its history).