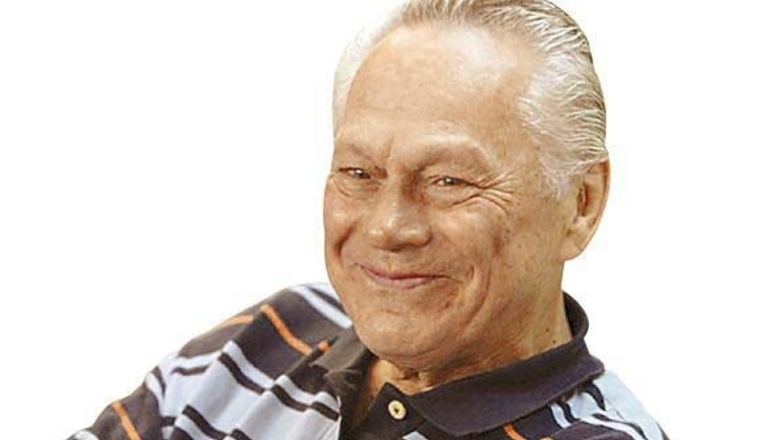

During the 1980 Olympics, Yuri Titov was the president of the International Gymnastics Federation and was heavily involved in the organization of the Games. He talked to Gymnastika about the experience for the 40th anniversary of the Moscow Games.

A: Forty years have passed but we admit that the success of the Moscow Olympics was enormous. Everything is fresh in my memory as if it happened yesterday. I want to congratulate those who are still with us – the organizers, and, most of all, the athletes and the coaches, and not just the Soviet ones but also those who came from abroad. And those who started the project “1976 Moscow Olympics”. No, I’m not mistaken. It was the first attempt to win the bid for the Summer Olympics in Moscow. Without that first attempt, the second one wouldn’t work. Who was responsible for that project? I don’t know everyone but it was a team of young and energetic people. The authorities supported the idea, since it appeared back in the beginning of the 1960s, following the successes of the Soviet team which entered the Olympic family as a serious competitor right away. The bid was submitted to the IOC in 1970. Back then, six years were given for the whole preparation and not seven, like now. It was necessary to show that Moscow already had a high number of sports facilities and the city’s infrastructure was capable of handling hundreds of thousands of tourists and that traffic jams would not happen. That Moscow already had skilled sports experts. And that the government would guarantee building the missing facilities and keeping the participants and the tourists safe. It was a colossal amount of work but we did it together! We were true Sixtiers.

Q: That bidding committee lost to Montreal and went into the new race four years later.

A: The IOC became sure that Moscow was capable of hosting the Games. I think that was the biggest legacy of the first bid. We were allowed to enter the bidding again. The idea wasn’t dead, we didn’t give up. Of course, we had to repeat the same work, partially travel the same road. Although… Life didn’t stay still. The IOC requirements change every year. So, we had to go through all the procedures from start to finish, while, of course, taking into account the past experience and mistakes. But the bidding committee team was mostly the same. Inspections were being held all the time but the foreign experts were shown the updated potential of Moscow’s infrastructure and that of the country as a whole. Sports facilities were the most important, of course. The fact that Moscow gained experience was a plus – there was the legendary World Festival of Youth and Students in 1957 which basically started the history fo the Lenin Stadium (called Luzhniki now). Komsomol was hosting youth festivals – Japanese-Soviet Friendship, Mongolian-Soviet Friendship, Finnish-Soviet Friendship – over a thousand participants, that’s big number. Komsomol played a big role in the preparation [of the Games].

Q: Gymnastics was always at the top in the USSR…

A: Besides big victories, we also hosted the 1958 World Championships. At the time, there were also a prestigious competition in Moscow under the wing of two newspapers, Moscow News and the Japanese Chunichi Simbun. That’s more than 30 countries [participating]! And a week later, the same gymnasts, after a bit of rest, took charter flights to Riga where they fought for the Amber Horse and Amber Beam prizes.

Q: Our people have a distinctive feature, when they’re organizing something. It takes them a long time to start but they end up way ahead everyone. Moscow-80 proved it to the whole world. How did they manage to do that?

A: When Michael Morris Killaning, the IOC president, showed the piece of paper with “Moscow” written on it to the IOC, it was a victory but not the main one. Everything was still ahead. Because there was a real danger not to finish all the sports facilities in time set by the IOC. The head of the USSR Sports Committee Sergei Pavlov would express his unhappiness to the Games organizing committee more and more often. I was responsible gymnastics, of course. Once, the Minister of Interior Nikolai Shchelokov said, “Get gloves and hard hats and go to the building site”. And all of us, each responsible for our own sport, became builders. Some inspected building sites, some – renovations. But our legendary Larisa Latynina was the leading person in the organizing committee. I was responsible for Luzhniki, the main Olympic site which had existed for a long time and needed renovations, and for the well-known training center Round Lake. At the time, many of the facilities required major repairs. It was decided to build a two-story hotel and to fix the main gym. At some point, I even did some electrical work. In the winter of 1979-1980, I came there as an inspector. The builders and soldiers (common for that time) were sitting idle. I asked, “What happened?” They responded, “And what can we build here? We can’t see anything, there’s no power”. True, the days are short in the winter. I turned back and went to Moscow to buy some electrical cable. It was quite long, about 100 meters. I personally bought it and brought there. So, if we’re talking about the tangible legacy of the Olympics, many things were built brick by brick and nail by nail. I’m talking about all of us.

Q: But there was a risk that all those efforts would be futile, right?

A: True, people wanted to extinguish the fire of the Moscow Olympics. There were voices arguing for a cancellation or postponement of the competition. Yes, those Games were not easy for us. Of course, the USA played the first violin in the orchestra of the naysayers. But we didn’t just hold our own, we also showed an unprecedented level or organization and hosting. We thought of everything. Not just the main facilities that are seen by everyone but also the training halls. For example, in Tokyo, long before us, the delegations lived in ex-US army barracks with rattling iron closets. Looking ahead, let’s also remember Los Angeles-1984 which I, one of the few of our compatriots, managed to see thanks to my international job. There were cardboard and plywood partitions everywhere. Or, another example from there. They built the training gym. And, about 50 meters from it, the competition hall. I asked a reasonable question, “And how will the gymnasts get from one to the other?” The hosts replied, “Easy, by walking”. I asked, “So, [the same place] where all the spectators are walking, then?” Honestly, I was so outraged that I, on behalf of the FIG, initiated building a temporary suspension bridge. It was later jokingly called “Titov-bridge”. They just couldn’t think of the simplest things. Juan Antonio Samaranch, the IOC president at the time, asked me, “Why are you attacking them?” But what was the issue? The organizers there do not care much about the look or properties of such facilities if they’re not being filmed. They were trying to save money on everything, as if the country was deep in a [financial] crisis.

Q: What were Moscow’s strentghs?

A: Well, let’s take the Olympic village which was built from scratch unlike the ones by the hosts mentioned above. It was not so far from the city center and especially from Luzhniki – in Ramenskoye, which was a quiet isolated neighborhood at the time. There were many specially built buildings. Delegations were given everything needed for their rest, since it’s impossible to handle exhausting training and competition days without rest. The organizing committee didn’t forget the entertainment for the main guests and both the Olympic facilities and the city were well-decorated. There was a club for meeting people and dance parties. Getting praised by the guests is the best evaluation of the work. Olympians from 80 countries thanked Moscow-1980 for the hospitality.

Q: Today, there are only a few international sports officials from Russia. But you were the FIG President, the head of the organization which was well represented at the Summer Games. At the same time, you were kind of caught in the crossfire…

A: This was my second term as the FIG president. I fought for holding the pre-Olympic FIG Congress in Moscow. At the end, I managed to achieve that, it took place at the Moscow State University building in Lenin Hills. American Frank Bare was running against me. I asked him to stay as a vice-president but he refused. We were working well together but he wasn’t making all the decisions – it’s likely that he was persuaded to leave by people at home. Going back, I remember my first congress as the president. I was surprised. More than half the delegates didn’t know anything about the agenda or the documents. And, I guess, the unhappiness expressed by my face was impossible to hide. There was a member of our delegation, a woman older than me. During a break, she told me, “Yuri, this is not a party meeting. You’re taking everything too seriously. No one owes you anything”. As we approached the 1980 Games, I was trying to get rid of any subjectivity in judging, in order to avoid rumors. The strongest had to win in Moscow. At the meeting of the judges from Socialist Bloc countries, I said, “You can show loyalty to the ideals of the Warsaw Pact, but don’t ruing your image on the international level. What for? If you get cocky, your score will be thrown out. It’s one thing to add an extra tenth, but [you need] to stop with that”. This one tenth backfired for me – journalists from West Germany learned about it and cornered me. Although I’m sure that those who won in Moscow were the best in that moment.

Q: During that romantic time, did people still believe that sports were separate from politics?

A: The boycott of the 1980 Olympics was not the first time that refuted this kind saying. At the 1956 Games in Melbourne, where I won gold, I realized that politics and geopolitics were somewhere close. Then, in Australia, White Guardsmen suddenly came to the Olympic Village. With a Tzarist Russia flag. And Vlasovtsy, too, all with accreditations. There were two kinds of them – peaceful and aggressive. The peaceful ones would say: “Don’t believe them, we were lied to, the command headed by General Vlasov got us surrounded. And they betrayed all of us”. But the aggressive ones, on the contrary, promised to “come back”. Or how about the story about Vladimir Kutz who got a live dyed rat as a present in a box? When he won gold in 5000 and 10000 meters fighting British Gordon Pirie? Yes, politics was always present. Both terror and provocations. Starting with Hitler who used the 1936 Games as a platform for his speeches. The USSR didn’t go to the first postwar Games in London in 1948 – the relationship with Great Britain left much to be desired. Either they weren’t waiting for us, or our people hesitated, which is also possible. This is how it goes – attention of the printed press plus the rapid growth of the TV and, as a result, starting from terrorists and ending with political heavyweights, everyone tried to attach themselves to the five rings and leech off this platform. Of course, four billion people are watching the competitions now, it’s a great opportunity to get “famous”.

Q: And now we’re approaching the most painful topic, the boycott.

A: The boycott of the Moscow Olympics and the mirror response to Los Angeles four years later – yes, it was likely more about politics than about safety. I personally saw a magnet with the five rings, Moscow mascot Mishka and words “Kill the Russian bear”. But on our side, 1984 was more of an emotional propaganda response. Afterwards, the Foreign Affairs Minister Andrey Gromyko practically admitted that the USSR’s decision not to send the team was a mistake. And that we lost more than we gained. I didn’t see this document and no one spoke about it directly but they whispered about it on the margins.

Q: In our days, it’s impossible to imagine a world-level competition and especially the Games without US gymnasts. What about then?

A: At the time, Americans didn’t make all the difference. Now they got back what they lost by leaning on their school, system, and traditions. In 1978, at the World Championships, the USA won medals and practically on the eve of the Moscow games, two American gymnasts were already targeting victories. And we expected competition from Japan and North America on the men’s side. But then the decision of the American government was announced by the president Jimmy Carter.

Q: And for women, the power balance was even more unclear, right?

A: In order to talk about the women’s competition in Moscow, you have to cover almost the entire decade. In the beginning of it, Czechoslovak gymnasts competed well. And Nadia Comaneci is remembered by everyone. The first triumph of the Romanian gymnast was her performance at the 1975 European Championships. Nadia showed superiority in almost everything, taking five medals, all gold but one. Specialists and even regular spectators noticed right away that the technical difficulty of her elements was higher than that of other gymnasts. Our gymnast, Nellie Kim, also competed well, also won five out of five possible medals, but only one of those was gold. Comaneci was known for infallible precision, graceful style and ease of execution. And the question was whether the young princess would become queen at the upcoming Games in Canada. And she did. Just as a year ago, our Nellie Kim with improved and upgraded routines was right on her heels. But, I guess, it was not possible to catch up with the Romanian in everything, there was not enough time. Even though Nellie took not one but two golds from Nadia this time. A year before Moscow-1980, at the European Championships in Prague, they met the third time. Our number two was Elena Mukhina and Romania’s was Teodora Ungureanu. Comaneci won the all-around but young Mukhina won silver this time, Kim was behind her, and Ungureanu ended up out of medals. Event finals started with vault. Our Kim won first place, Comaneci – second. Bars revealed a complete tie in the scores of both athletes. In gymnastics, two golds were a normal thing. And now, attention! Nicolae Ceausescu, the leader of Romania, personally gets in touch with the head of the Romanian delegation Nicolae Vieru and orders to withdraw Nadia from the competition, promising to send his private plane. It seemed to him that there was a bias against the Romanian star at the competition and the judges were giving her low scores on purpose.

Q: What did you do as the FIG president?

A: I called the Romanian ambassador in Prague and tried to explain that six judges from different worked on every event, that there was the Jury of Appeal and there were no rule violations in scores. In response, the ambassador pronounced me persona non grate in Romania. All the medals Nadia won (two golds and one silver) were sent to her. But she left the European Championships and with this, devalued it a bit. At the 1979 World Championships Comaneci won individual medals of the highest order and Romania became the best team for the firs time. [1]

Q: How was USSR responding?

A: The coaching staff understood that our competitors were getting really close. The Japanese, the Czech, and especially the Romanians were showing by example that difficult elements were the most important thing. There is such a term “dynamic posture”. Of course, it includes everything together. Any spectator and definitely a judge will see errors. If legs are bent at different angles, for example. We recruited serious support – ballet choreographers. For example, we were visited by such stars as Maya Plisetskaya and Vladimir Vasilyev. Our Masha Filatova who competed on the national team was small and not ballet-like at all, in her routine, she was rolling around like a ball to drum music. But a legendary ballet choreographer put her in relevé and gave her Chopin’s music. And suddenly this “thumbelina” became more elegant than many… But, right before the Games, something horrible and irreparable happened in gymnastics which practically everyone knows about. Rising star Elena Mukhina got injured at the training camp in Minks. I know that she had few chances to even survive! The skilful actions of the doctors saved her.

Q: It’s a horrible and unfair case but it’s impossible not to talk about it.

A: Lena Mukhina was not making the team that year – she didn’t have the best season and was only 9th. But she was a world champion, among the great ones already. So, an exception was made for her – she was invited to the camp. I was working in Moscow but visited the team sometimes. Her personal coach Mikhail Klimenko came to me – he wanted to give me the message that his pupil was getting better and was worthy of being put on the team. She stayed at the training center in Belarus without him for only one day. We all know that training without a coach when he’s temporarily away is not a big deal. But anything can happen. Lena herself later told me: “I felt that I did the element easily and freely and raised my head – to see. But you need to tuck your head in to roll out. My arms bent and head bumped into the floor.” Neck vertebrae got shifted out of place. People say that after such falls, there’s only a 2-3% chance to survive. But Lena was being saved by the whole country. Three of our best surgeons took part in it, Professor Arkady Livshits did everything possible. Her life was saved but a career and a full life were out of question. Of course, this depressed the team. But, as you see, our team still won 9 out of 14 golds.

Q: Did you believe in the team’s success in the final stage of the preparation?

A: The team was good. Even though there was a lot of competition. We expected that there would still be competition, no matter whether the boycott happened or not. We had the results from previous years. Japan had a fresh team with good routines that competed we;; in 1978. But they went down after that. In 1979, American Kurt Thomas appeared. He got all the medals for everyone. And it became clear that if he had repeated what he did, it would have been hard for us. Bart Conner, his teammate, was also a threat. The efforts of the two of them could have been enough for success. But everything happened differently. At that moment, both of the countries mentioned above insisted on moving the Games back to Montreal. We were left with Bulgaria and Hungary and they won some things as well. And we had a Russian trio that was formed in 1978 – Nikolai Andrianov and two Aleksandrs, Tkachev and Dityatin. We were confident in their strength and the competitions during the preparation period were consistent. And why? Because all that time we were preparing the routines while taking into account the strengths of the potential competitors and recent failures. We knew that a clean easy routine would lose to a difficult one that had errors. And when the rivals didn’t come, it turned out to be not a competition but a demonstration of power, some sort of a manifest of Socialist countries. It was more complicated on the women’s side, even though the Socialist block was also at the forefront. We were expecting a battle with Romania and East Germany. But these teams were lacking gymnasts for team-wide successes. And we had new stars Natalia Shaposhnikova and Elena Davydova to help Nellie Kim who had experience. The fight was really tough. Floor. Maxi Gnauk and Nadia Comaneci got the same score and went ahead of Shaposhnikova. They started hugging – no one’s offended, they both get gold. During this moment, Davydova finished her last event. And in the end, the gymnast who hadn’t been a threat to anyone before went ahead of both of them. This was one of the most dramatic moments of the Moscow Olympics. But if someone thinks that we won more medals because of the boycott, I will disagree with them. We took the competition into account and were ready for any challenges. They didn’t come to compete against us, oh well, what can you do… No matter what happened, there are no what-ifs in history.

[1] Titov’s memory is failing him here. The story about Comaneci leaving the European Championships happened in 1977 In Prague. Kim didn’t win gold on bars there, that was Elena Mukhina, who also won gold on beam and floor. Comaneci indeed won gold with the team at the 1979 World Championships but no individual medals – Nellie Kim was the World AA champion that year.

Además de fallarle la memoria a Titov, es un ser muy mentiroso y cruel con lo que le sucedió a la gran Elena Mukhina. Todos sabían que su lesión en la pierna era un impedimento para tener un buen desempeño, pero la empujaron y obligaron a ejecutar ese maldito elemento que la dejó paralizada, y mintió al decir que ella tuvo la culpa. Creo

Que a Titov tendrá que pagar por sus mentiras sobre Elena Mukhina.

Dios no está ciego ni sordo.