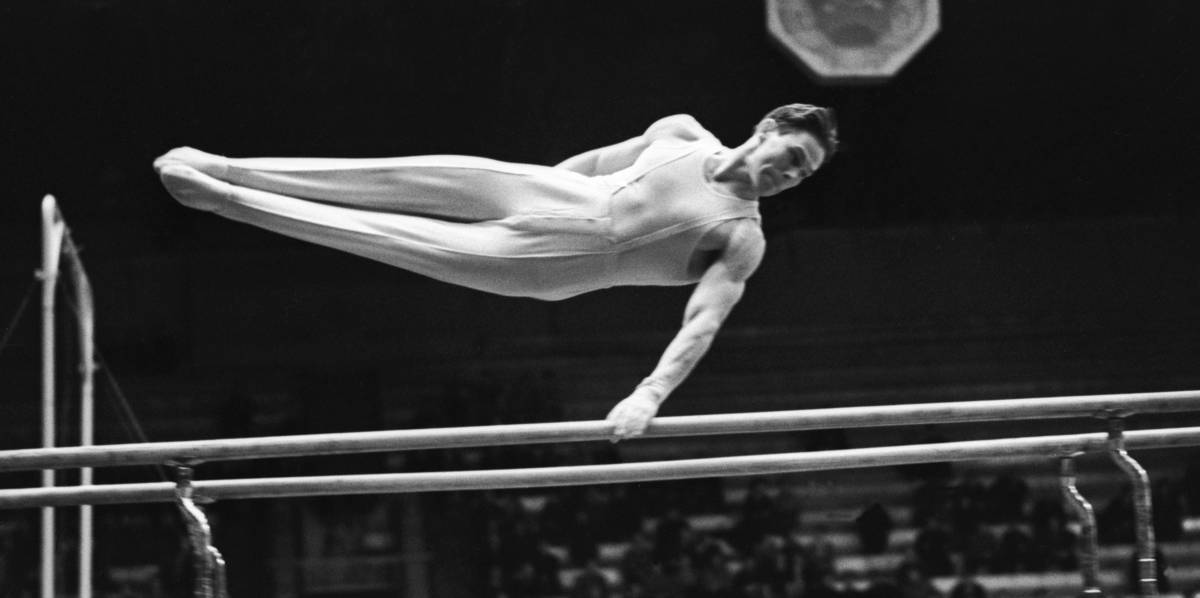

Three-time Olympian and former president of the FIG Yuri Titov turned 85 in November. He gave an interview to TASS on this occasion and talked about his career and the current generation of Russian gymnasts.

The current FIG President Morinari Watanabe congratulated Titov in person during a work visit to Moscow:

“We talked and remembered how we organized competitions in which out athletes actively participated for several years. I showed him a shoe I wore at the last Tokyo Olympics with autographs of all the Japanese gymnasts that competed there. I gave him a Mishka figurine, the Moscow Olympics mascot, which was made out of bone over 40 years ago. And he gave me, a Siberian man, a bottle of sake.”

Titov won Olympic gold as a part of the 1956 Soviet team and multiple silver and bronze medals but never the all-around gold:

“Talking about the Olympics, I consider myself somewhat a loser. At my first Games in 1956 in Melbourne, I got injured a few hours before the opening ceremony. We were waiting for our entrance at the nearby stadium, hiding from the heat, and when it was time to get down from the bleachers, I got an eight-centimeter wooden splinter from a broken bench stuck under my knee and it punctured a ligament in my leg. We took a cab and went to see a surgeon right away, he took the unfortunate piece of wood out and then I couldn’t fully train because of that injury.”

“In Rome in 1960, during the rings routine, my arms went numb for some reason. The routine was almost over but I lost the feeling in my right arm completely. I thought that I was going to fall and, indeed, my right hand slipped off the ring in the end. With only my left hand, I managed to do some sort of a dismount but didn’t get the kind of a score I planned to get. But I still managed to place third in the all-around then and I’m very proud of that result.”

In 1962, Titov became the all-around champion at the World Championships but a series of injuries prevented him from medalling in the all-around at the 1964 Olympics:

“Soon after the 1962 Worlds, I felt pain in my back during training. Only after two weeks of suffering, I got an x-ray, which showed that three of my spinal disks got ruptured and all the fluid got out of them. After that, a doctors expert committee determined I had a Group II disability [1].”

However, Titov found a doctor who tried physical therapy to fix the issue:

“It was torturous therapy, I was supposed to do it for two months but stopped one week early. Then I was sent to the Saki mud resort [in Crimea] which was the final touch in fixing all my spine issues. By that time, there are slight more than a year left until the Olympics and I managed to prepare during that time. I was put on the team again but a couple of weeks before the Olympics, I injured my arm and had to compete in pain during the whole Olympics. And my desire to perform as well as possible on floor despite the injury ended up in a big error when I landed a pass on my face. That was how I went from a favorite to a loser.”

The Tokyo Olympics took place 19 years after the World War II during which the USSR and Japan fought on opposite sides but Titov said gymnasts from the two countries did not feel animosity:

“Despite all the difficulties in the relationship between the USSR and Japan, Soviet and Japanese gymnasts never had issues in communication. We were always friends with them. With some, it even became a friendship of whole families. During the Tokyo Olympics, we would visit the Japanese gymnasts. They had TVs in their rooms and empty beer bottles on the floor. We asked them whether they drank during the Olympics and they responded that beer helps them fall asleep faster. The Japanese often organized tours for us, fed us. There was true friendship between us.”

As the president of the FIG, Titov had to work during two boycotted Olympics – in 1980 and 1984. He was against both boycotts:

“The Italians, French, and British, despite the pressure from their governments, still came to Moscow. But the Japanese and Americans had to watch the Olympics on TV screens. Almost all the heads of national federations whose teams couldn’t come to Moscow expressed to me their anger at their governments that prohibited the athletes from going to the USSR. On the eve of the 1984 Games I had to listen to angry rants again, but this time it was from the colleagues from Communist Block countries the governments of which had to support the Soviet Union’s decision not to send athletes to Los Angeles. As you know, the refusal to go was based on the American side allegedly being unable to guarantee the safety of Soviet athletes. I was even asked to check with the emigrants I knew whether there was any real danger for our athletes. But I only heard from them the reassurances that there was none. The Soviet Union embarrassed itself with the decision to boycott the 1984 Games. As the head of an international federation, I was in Los Angeles during that Olympics. People would ask me, laughing in my face: so, the Soviet government is afraid to send their athletes – does it mean they don’t care about me, then? Although, to be fair, I was constantly under the surveillance of local intelligence services, I felt that I was always followed.”

Titov asked the government to send at least 10 of the greatest athletes:

“After all, I doubt anyone would dare to offend them, out of respect for their achievements. If ten people had come, then there would have been no boycott on the part of the USSR. But, in the end, there was a complete boycott.”

Titov is still closely following gymnastics competitions and things that while Russian men have a good chance for gold in Tokyo, the postponement of the Olympics might make things harder for them:

“I really want our guys to compete as well at the Tokyo Olympics as they did at World in Stuttgart. One of the Japanese gymnasts recently showed a very difficult element on high bar and went one step ahead of everyone else, no one ever showed this element before. One can assume that the Japanese have other surprises in stock as well. We also shouldn’t stay on place, otherwise it will be very hard to compete with the,. I think that the postponement of the Olympics by a year makes the task of winning gold in Tokyo harder for Russian gymnasts. But our guys shouldn’t change their routines by this point, there’s too little time left until the main competition. There are great gymnasts who are capable of many things on our team. I’m talking not just about Nikita Nagornyy and Artur Dalaloyan but also David Belyavskiy and other guys.”

[1] In the Soviet Union, disabled people were classified into three groups which determined the benefits they got. Group II was in the middle – severe enough to get certain benefits but able to move on their own (possibly using mobility assistance).